The annual Tundra Spring Migration is just about over. The swans left their winter home in Chesapeake Bay and started arriving here at the end of February. This is the first stop on their journey to the Arctic. They land in the wet farmers' fields where they can find food and rest up for the next stage of their journey. Large groups of swans have been in the area for the past three weeks. They're also in Aylmer, at a wildlife sanctuary where food and water are both available.

Unlike other years this time the light has been excellent, with blue skies, patches of cloud, and soft golden evening light rendering the swans even more beautiful.

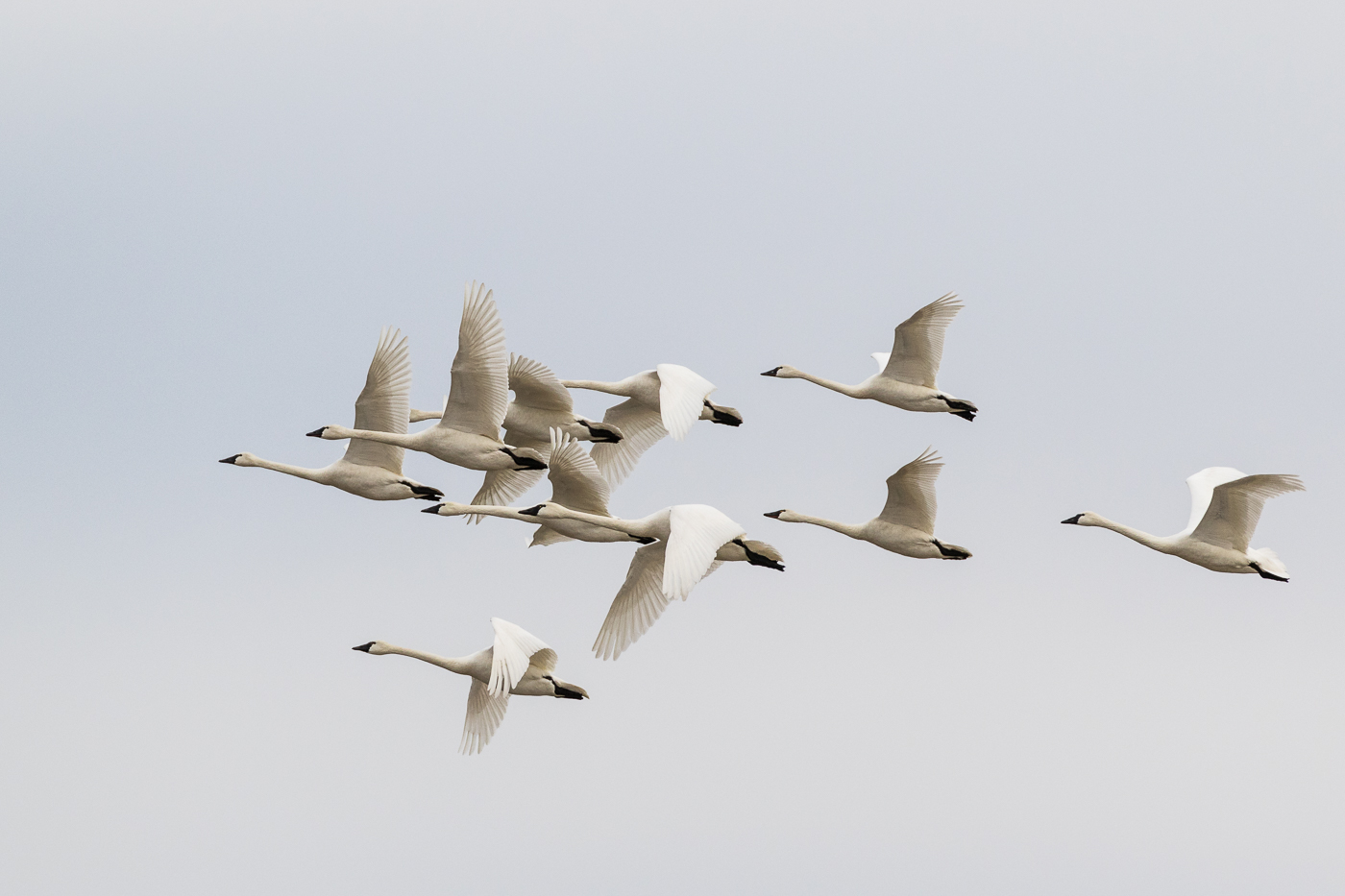

They tend to fly in groups and can be heard long before they're seen. Watching a large group of tundra swans flying overhead is an amazing sight.

These are large birds, almost 5 feet in length with a wingspan of 5-1/2 feet. Males weigh in at 7.5 kg and females a little less at 6.3 kg. They take their time in choosing a mate but once chosen they pair for life.

This group is taking off for the next stage of the journey west and north.

They're active on the water, interacting with each other, moving around, making loud sounds. They run across the water as they prepare to fly from one section of the pond to another.

Despite being large birds they land easily and elegantly, although sometimes nearby swans and geese get swamped. Here three swans land among a group of resting swans and geese, and startle a dark morph snow goose into flight. The goose flew a few feet away and quickly settled back down.

When the birds come in for landing they brace their legs, lower their rear ends, skim across the water for several yards leaving visible trails, and slowly retract their wings as they prepare for a resting position on the water. The settling of the wings occurs gracefully over several seconds.

Several swans landing in the middle of a large group already on the water

A family of four arriving late in the day and getting ready to land. The two younger birds, the ones with brown heads, were born in the Arctic last year and are undertaking their first migration north. They remain with their parents for at least one full migration.

This year's migration is coming to a close. As always I've enjoyed seeing and photographing these strong, beautiful birds. I wish them well on the journey to their Arctic breeding grounds and look forward to seeing them again next year.